Hell Hotel: San Lucas Prison

For the most incorrigible misbehavior, like killing another prisoner, inmates at the San Lucas prison island were lowered into “the hole” — literally a hole in the middle of a big concrete disc on top of what was designed to be a cistern to hold rainwater.

This underground dungeon actually did hold water, sometimes up to a man’s midriff, so the unfortunate souls condemned to this gruesome punishment were unable to sit, much less lie down and sleep, for however many days and nights they had to endure this torture.

“You had to stand for days, and sometimes they had people in there for like a month, and they came out either dead or crazy,” said Vigdis Vatshaug, the Norwegian tour guide who led my family on a fascinating and disturbing tour of one of the most brutal prison islands on earth — right here in the happiest country in the world, in the Gulf of Nicoya, a short boat ride away from Playa Naranjo.

San Lucas Island is best-known as the setting of “La isla de los hombres solos” (“The Island of Lonely Men”), a novel written by the former inmate José León Sánchez, a Tico accused of stealing religious icons from the Basilica of Cartago who spent 30 years imprisoned here.

In this case, the truth is every bit as strange as the fiction. As soon as we disembarked from our boat at the rusty old pier, we climbed the steps to the “Camino de Amargura,” the “Road of Bitterness” that greeted new inmates upon arrival during the years the prison was open, from 1873 to 1991.

Flanking this road are two small, dirty rooms, now filled with bats, where new arrivals were welcomed by being corralled into a filthy, crowded enclosure with no place to sit or sleep except the floor. They were given very little food, and the bathroom was a bucket in the middle of the floor. New arrivals spent several days in this dungeon — letting them know what lay ahead, and undoubtedly making them thankful when they were released to larger quarters with separate latrines.

“People were not punished for doing something wrong,” Vigdis said. “They were punished so they wouldn’t do anything wrong.”

The ball and chain

Each inmate was issued a ball and chain attached to his ankle, with the size of the iron ball commensurate to his crime. The largest iron ball might weigh 50 pounds, and these were never removed. Prisoners oddly took pride in keeping their ball and chain clean, according to Sánchez’s book.

“They all kept polishing and keeping their ball and chain very nice,” Vigdis said. “They never would drag it because then it would be dirty; there was a pride in having a very nice ball and chain.”

In the worst cases, Vigdis said, two men were shackled shoulder to shoulder, so that neither man could sit, lie, walk or void his bowels without the other man at his side.

Some men spent decades here, and a great many died in this desolate place. Vigdis said an astonishing 20 percent, one out of five, died in their first year.

A few men managed to escape, having removed their shackles with tools they were given to break rocks. They had to brave strong currents to swim to the nearest island, or even to the mainland, but Vigdis said all escapees died or were recaptured.

The brave hooker

The happiest story we heard was about the day the prostitute came. Vigdis related a tale from the book about a prison commander who hated homosexuality, which was rampant on a prison island for only men.

The warden decided that the only way to put a stop to all the sodomy was to bring in women. So the guards went to Puntarenas (also known as “Putarenas”) and recruited prostitutes to service the prisoners.

“And the prisoners were of course excited,” Vigdis said. “They cleaned up the best they could, and were making little presents for the ladies.

“So the boat comes back from Puntarenas and it’s empty — because these prostitutes have only heard of this prison as a very dangerous place, with brutal criminals, murderers, rapists. But they tried again the next Sunday and one woman came. And the guards said they put her in the visitation house, and everybody got in line, and they decided how much time they had with her.

“She went back to Puntarenas and said the prisoners were all well-behaved and they all loved her and said she was beautiful and everything, so the following Sundays there were more coming in.”

My girlfriend, Guiselle, who used to live in nearby Paquera and visited this island many years ago, said the youngest, bestlooking prisoners were taken as lovers by the toughest inmates, and if they were unfaithful, they were killed. Vigdis said several men were forced into prostitution, or did it willingly, servicing anyone who could pay with a bowl of food, a shirt or whatever.

The walls of the nine cellblocks here are covered with graffiti, including pornographic pictures and forlorn comments. One note says, “Kneepads and bibs sold here,” signed by the gerente de ventas, the “sales manager.”

One striking drawing portrays a larger-than-life-size woman in a sexy pose, wearing a bikini that Vigdis said was reportedly painted in blood.

“Some say that he cut himself every day to paint again and again, and other stories say that he cut other people to collect blood,” she said.

Guiselle, who once met a former San Lucas prisoner, said he told her that someone killed another prisoner here and used his blood to write on the wall: “This is how I’m going to die.”

It’s hard to separate truth from legend here, as the prison’s log books were thrown into the sea years ago. Vigdis is aware of one nonfiction book about the prison, “Una historia sin fin,” “A Story With No End,” but she has never been able to find it. Most of her information comes from Sánchez’s novel and from the oral histories related by former guards, prisoners and visitors.

Laundry service

Inmates were issued a striped uniform upon arrival that had to last them two or three years. In the early days, laundry service was as nonexistent as medical attention, and of course people smelled pretty bad.

“So a lot of the prisoners walked around naked because they had lost a shirt in a bet over a piece of bread,” Vigdis said. “They could only wash [clothes] if they were on the beach, in salt water, but the only fresh water they got was to drink.”

If a prisoner died, other inmates could buy his clothes with some of their food.

“And the people that died, they were often sick and had infection and lice and so on,” she said. “And you were so happy because it was a better shirt, or maybe you didn’t have any, and you’re wearing the sweat and the blood of someone who just died.”

The architects of this island were French, who were experts in prison islands (look up Devil’s Island, or read the book “Papillon”). The worst of the horrors here date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though a nationwide prison reform in the 1960s eased conditions here considerably. Balls and chains were abolished, and some prisoners were allowed to build crude houses, plant gardens and raise chickens.

A suspicious fire

There is a beautiful little church here, newly renovated, though it is locked up. Adjacent to it, there used to be a threestory casona, with bedrooms and offices for the warden and guards — although it made national news when this building was burned to the ground on the night of Nov. 24-25, 2017. Speculation has it that illegal fishermen may have burned the house as payback for the government’s confiscation of their fishing equipment.

The casona looked out on a courtyard containing the concrete disc with “the hole,” and just beyond that are seven cellblocks that housed perhaps 100 people each.

The people in the cellblocks could hear the screams and cries of the wretched people standing in water day and night in the hole. And meanwhile, all the prisoners could smell the delicious food being served in the casona at dinner parties for the commander and his guards.

Costa Rica’s most miserable allinclusive resort was finally closed in 1991, its inmates relocated to other prisons. José León Sánchez was declared innocent of the Basilica crime in 1988, and today he is Costa Rica’s best-known writer. He is still alive and living in Heredia.

“Are there any ghosts here?” I asked Vigdis.

“There are lots of ghosts,” she said.

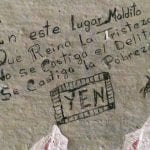

One graffito on the wall, in neat handwriting and perfect rhyme, says:

En este lugar Maldito

Que Reina La Tristeza

No se Castiga el Delito

Se Castiga la Pobreza

A free translation:

In this God-forsaken place

Of sadness all the time

It’s not crime that makes the case

It’s poverty that’s the crime