I’m going to step back in time to April 1977 to Pier 32 in Honolulu where I watched a cargo of potato sized rocks discharge from a Liberian registered mining ship named the Sedco 445.

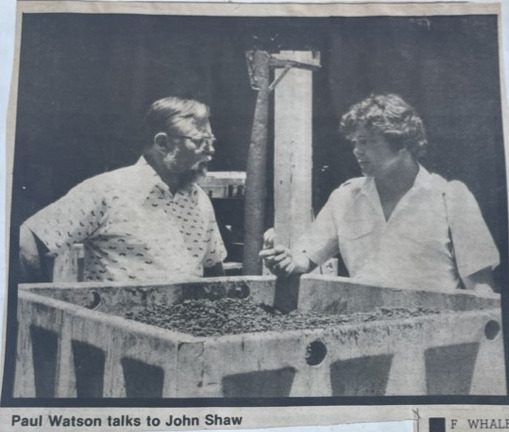

John L. Shaw, the President and General Manager of Ocean Management Inc. gave me a guided tour of the Sedco 445, the first ship to carry out a deep-sea mining operation.

The Sedco 445 had just returned from a mining site 800 to 1,000 miles southwest of Hawaii where it had brought up a continuous stream of material from a depth of 17,000 feet or three miles.

I picked up a rock that resembled a black potato and Mr. Shaw informed me that each of these rocks took over 200 million years to form on the seabed, and contained up to thirty different minerals with three quarters of the content of each nodule being nickel.

According to Shaw, the nodules formed over millions of years as falling debris like sharks’ teeth or fish bones acted as nuclei to gather trace minerals. The estimate is that the nodules grow about one millimeter every thousand years and in some areas of the benthic seabed there are billions of these potato sized rocks and each one is teeming with minute marine organisms.

The exploratory voyages were inspired by John L. Mero in 1965 with his estimate of vast ferromanganese (Fe-Mn) nodules in the Pacific Ocean. He speculated that the Pacific seabed contained a limitless supply of metals including manganese, copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, zinc, and molybdenum. That was enough to make huge mining interests salivate with the possibilities for exploitation.

Since 1965, Oceanographers estimated that these nodules could contain up to two trillion tons of mineral ore, more than all the deposits to be found on land.

On April 19th, 1977 I watched the Sedco 445 depart from Honolulu to return to the mining site to recover a second cargo of nodules, experimenting with a second method of nodule recovery.

The first test was successfully carried out with a system of hydraulic pumps. The second test created a wet vacuum to suck up the nodules from the ocean floor.

I expressed my concern to John Shaw and asked if they had conducted any research on the possible ecological damage. They hadn’t.

His primary concern was economic, and he told me that the current price of nickel could not justify full scale exploitation.

“We have the capability now,” said Shaw, “but aside from the political delay, the current nickel market is down. We can afford to wait.”

In fact, in 1977, it was in the interest of INCO (International Nickel Company) to wait. A 1977 report from the U.S. Treasury Department reported that, “INCO is out there as a hedge against what would happen if all those nodules flood the nickel market. INCO probably wants to stifle ocean mining.

INCO as the dominant world company depended on maintaining control of the international nickel supply.

INCO’s vice-president at the time in charge of ocean mining, Alfred Statham confessed to the U.S. Senate committee that, “the fact that we are the only consortia may give us a different perspective.”

Quite willing to do battle in 1977 with INCO were four formidable consortia all separately attempting to grab a large portion of oceanic territory for themselves. In addition to INCO’s longtime rival, the Rothschild owned Le Nickel SA., three newcomers to nickel mining entered the picture. Kennecott Copper Corporation, the U.S. Steel Corporation, and Lockheed Aircraft.

U.S. Steel, the largest nickel and manganese consumer in the world, was hopeful that deep-sea mining would provide two essential alloys to enable the company to break off its dependency on INCO.

Lockheed, the operator of the Glomar Explorer, the ship built by Howard Hughes for the CIA was hopeful that deep sea mining being a highly technological industry would yield large government subsidies.

My interest at the time was the ecological impact. Nickel composes 1.5 percent of the nodule content. 70% of the recovered material is worthless waste.

Mr. Shaw told me that “nodule mining is environmentally safe, there are virtually no environmental side effects.”

He added, “We had Federal inspectors from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) with us, they witnessed our operations and noted approval. They observed the situation and found no serious environmental problems.”

However, Dr. Robert Burns, one of the oceanographers who accompanied the Sedco 445 explained, “If I were he (Shaw) I’d probably interpret our findings that way. It is of course in his interest to do so.”

Burns explained that only one actual deep-sea mining operation had been observed, the very one he had recently observed on the Sedco 445. Burns said that it was too premature to make a definite statement one way or another.

“It was a short-term effect to scale. There was a lot of muddy water. We had not seen any sign of pollution but in a large-scale operation, we can’t yet say what the effect will be. Anyone who says otherwise is just whistling dixie.”

Other highly reputable and respected scientists at the time were in fact whistling their opinions.

According to a report published by Yale oceanographer Dr. Karl Turekian, if the waste is discharged on the surface, the residue may take years, even decades to reach the bottom. Ocean currents will spread the dust, silt, and debris over wide tracts of the Pacific. Turekian estimated that if all the then planned mining projects were allowed to proceed and are in operation by the mid-Eighties by the end of the century, several hundred thousand square miles of the Pacific could be contaminated.

Fortunately for economic and political reasons that prediction was not realized.

Yet now nearly half a century later, that threat now has the potential to be unleashed.

Metal tailings from the crushed nodules could be consumed by fish, whales, and other sea life with potentially harmful effects. Humans would be susceptible to heavy metal poisoning by consuming fish.

The slowly sinking sediment with adherent bacteria would consume oxygen in the deeper oxygen scarce benthic zones. The resulting competition for oxygen would have a detrimental effect on organisms living in such an environment. When the sediment finally reaches the seabed, three to four miles deep, the blanket of sludge will asphyxiate most life forms dwelling there. According to a study conducted by the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University, there could be serious consequences. The study pointed out that it would be unknown how long benthic species would need to repopulate devastated sections of the sea floor. It would also be unknown how the depletion of benthic life would impact the food chain through the entire oceanic ecosystem.

Another serious concern is the possibility that dormant spores or bacteria having lain undisturbed for eons could be released at the surface among life forms that have no immunity.

I spoke with Dr. Roger Payne in 1977 about these concerns and he added his view that heavy sediment could disturb the transfer of sound waves beneath the surface of the sea, affecting whale communication and migration and disrupting the social systems of whale species.

If the ecological concerns were falling on deaf ears, the potential consequences for the United States Navy were alarming to the US Defense Department. If whale and dolphin sonar is affected, so too would bionic sonar employed by the US Navy. This technology is designed to mimic sea sounds, especially whale sounds to avoid enemy detection.

The sleeper missiles that were placed on the ocean floor by the Glomar Explorer would also be affected and possibly rendered inoperable. The high frequency signals that would launch the missiles could be absorbed or deflected by drifting sentiment.

In August 1977, Assistant Secretary of Defense David McGilbert told a Senate Committee that his department could see no immediate need for mineral resources from the seabed.

“The Navy,” he said, “does not relish the prospect of having to defend the bulky and slow-moving mining ships on the high seas.”

Gilbert told the Senate that the Navy wanted the Law of the Sea to succeed. He also made it clear that to anger the them could result in the closure of essential straits and canals that naval ships use.

In 1977, the government of Hawaii was unconcerned about ecological consequences. Governor George R. Ariyoshi said the project would create jobs and investments. That was his sole concern.

John Shaw told me that “Hawaii is certainly geographically best situated, and I’ve certainly been impressed by the attitude of the industrial development people.”

In 1977, the Hawaii State Department of Planning prepared a paper called The Feasibility and Potential Impact of Manganese Nodule Processing.

According to this study the nodules could be transported in barges to Hilo harbor and pumped in slurry form through a pipeline, the waste would then be pumped back to the harbor and loaded in barges to be returned and dumped. The report foresaw no significant impact on the environment except in the case of an accident.

In addition to minimizing and downplaying the impact on the oceanic environment, the report completely ignored the fact that metal refining, especially nickel refining, requires vast amounts of energy and water and produces toxic fumes. A visit to the largest nickel mine in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada is all the evidence needed to see how toxic nickel refining is.

That is what I reported on in 1977 and for the last half a century, I have been watching the ever-looming threat of deep-sea mining. To date, the deep-sea environments have been relatively protected by the high costs associated with large scale industrial development, the concerns of the military and increasing awareness of the threat to deep sea ecologies that benthic mining will most certainly cause.

However, things are changing, and not for the good.

Since 2001, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an intergovernmental body in charge of regulating deep-sea mining in waters beyond national jurisdictions, has granted 31 exploratory licenses to private companies and governmental agencies. The organization is unlikely to approve commercial mining applications until its 36-member council reaches a consensus on rules regarding exploitation and the environment. Member states have set a 2025 timeline to finalize and adopt the regulations.

Today, the technology has advanced considerably since 1977 and the price of these metals has risen sharply providing both financial motivation and accessibility.

The mining industry sees a vast area with trillions of “rocks” easy for the picking. What the industry fails to see or refuses to see is that this is a vast living finite ecosystem that has evolved over hundreds of millions of years. These nodules are not renewed and mining will eradicate exceedingly large eco-systems, the machinery will produce high decibel sound waves that will have a devastating impact on living organisms and the silt will smother the life that survives and it will never recover, at least not for a few hundred million years.

In addition, sucking up the rocks, the industry is looking at scraping the sides of undersea volcanoes to extract the cobalt crust and digging deep into the benthic mud to extract massive sulfide deposits around hydro-thermal vents.

Deepsea mining will cause more destruction on the planet than the cutting down of Amazonia and Indonesian rainforests. But it will be done with no visible scars where the impacted ecosystems will remain hidden from view and will become huge extensive invisible dead zones and the impact on the planet’s atmosphere and ocean ecology will be immense.

How will it impact the already diminished populations of phytoplankton which provide up to 70% of the oxygen in the atmosphere? How will it impact the already diminished populations of krill, the foundation of the food pyramid in the sea? How will deep sea mining influence climate, the movement of currents, and the migration and viability of sea life? The industry has not answered these questions because there is no answer that they will acknowledge because such answers will expose them as harbingers of global destruction.

At present, there simply is no regulatory framework for mining inside or outside of economic exclusion zones.

Already territorial disputes are emerging. Norway and Russia both want to exploit the seabed of the Arctic Ocean. China is hungrily exploring how to exploit the South China Sea which will cause problems for the Philippines, Vietnam, and Japan, and this jockeying for control is on a planet where there are already over 100 unresolved maritime disputes.

Thus, we can now see a new threat to the stability of the life support system we call the sea, where acidification, species diminishment, plastic, noise, and chemical pollution are already seriously straining the biological processes that keep the ocean healthy.

It appears that full scale deep-sea mining could begin by 2026 and if it is allowed to do so, the global consequences could be catastrophic.