Cover Story – Ollie’s World or How a secret airstrip in Costa Rica fueled a global scandal

In 1987, President Oscar Arias won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating an end to Central America’s brutal wars. Oliver North and his shadowy friends wanted a very different outcome. Here’s how a secret airstrip in Guanacaste blew their cover.

In September 1986, five journalists from the Tico Times and NBC chartered a small plane at the Liberia airport and embarked on a bizarre mission — to find a secret airstrip in the Costa Rican jungle that was supposedly being used by U.S. intelligence operatives to arm the Nicaraguan Contras.

Ollie’s Point Surf Spot Link

The journalists were nervous about this undertaking, suspecting that the government was covering up secret operations by the US in Costa Rica, and they told their pilot that they were interested in photographing turtle-nesting beaches.

It was a short flight from Liberia to Potrero Grande (“Big Pasture”), a valley in what is today Santa Rosa National Park, on the northwestern Santa Elena Peninsula. Most of the land below had few signs of human impact, as almost all of it had been expropriated years earlier under the Daniel Oduber administration to create the large national park. There was one landowner, however, who had long refused to sell.

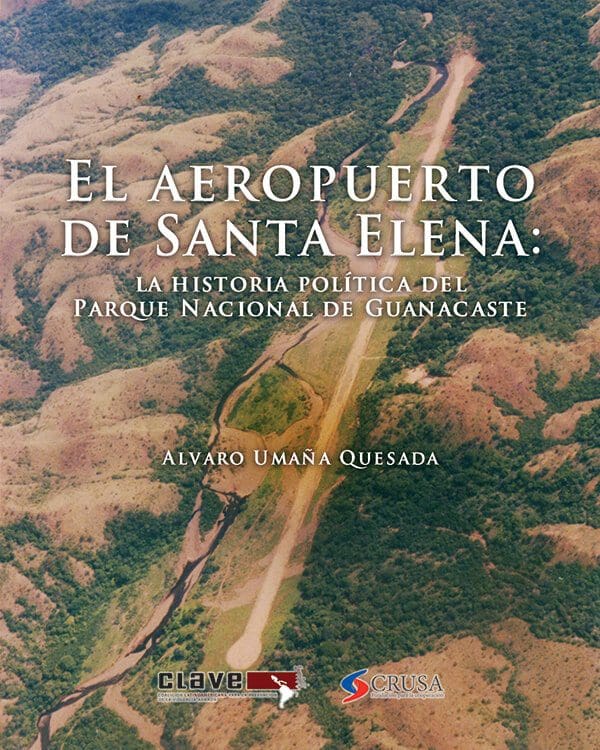

Near the surf spot known today as Ollie’s Point (after Lt. Col. Oliver North, the mastermind of this operation), they spotted their quarry: a mile-long landing strip in the jungle that had no good reason to be there.

“We went down the coast pretending we were filming the beaches,” said John McPhaul, a stringer for the Miami Herald who was also working with the Tico Times. “And when we got to Potrero Grande we had the pilot circle around it. It was obvious, it had huge tire tracks. It was in a valley, surrounded by mountains, and it opened on the beach.”

The reporters were by no means sure what their discovery meant. But their find would light the fuse of an international bombshell that became known as the Iran-Contra affair, the biggest scandal in U.S. history since Watergate.

And it all started in Guanacaste, the border province of a country that was officially neutral in Nicaragua’s brutal civil war. Costa Rica, which abolished its army in 1948 and had been considered a bastion of peace and democracy ever since, ended up playing a major role in one of the hottest battlegrounds of the Cold War.

A recent book by a former minister of the Oscar Arias government traces this improbable history in meticulous detail. Point West: The Political History of the Guanacaste National Park Project by Alvaro Umaña Quesada, the minister of environment and energy in the late 1980s, extensively documents the evidence for a Contra gun-running (and drug-running) operation in Guanacaste from both the Iran-Contra hearings and his inside experience with the shadowy project.

He also documents Arias’ steadfast resistance to the Reagan administration’s use of this secret landing strip in Costa Rica.

“Fortunately for future democracies in Central America,” the book says, “President Arias prevailed, and he was able to derail the U.S.-backed war effort and save thousands of lives. His resistance to the Iran-Contra affair then opened a unique historical window of opportunity and allowed him to launch his peace initiative in the region, for which he was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987.”

Regime change

Elections have consequences, and the election of Oscar Arias as president of Costa Rica in February 1986 would prove to be a mortal blow to a clandestine war orchestrated by the most powerful country on earth.

The previous Costa Rican president, Luis Alberto Monge, had declared Costa Rica neutral in the Nicaragua war, yet he looked the other way as activity in support of the Contras took place on Costa Rican soil. It was Monge’s minister of public security, Benjamin Piza, who had agreed to let U.S. operatives build a secret airstrip in Potrero Grande to support the Nicaraguan rebels that Ronald Reagan would later call “freedom fighters.”

The only thing Piza asked in return, according to Umaña’s book, was a brief meeting and a photo op with President Reagan in the Oval Office of the White House, which took place on March 17, 1986. Oliver North was present in the room, and in fact he wrote Reagan’s talking points for the meeting.

Later that day, Piza and North’s right-hand man, a one-eyed Vietnam vet named Richard Secord, met at the Four Seasons to draw up a document granting the right to build an airfield at Potrero Grande.

The mendacious document claimed that “Udall Research Corporation” — a fictitious company created by North and his team — was granting “the Government of Costa Rica” the right to build an airstrip on its property. In fact, it was the other way around — a Costa Rican government minister was granting U.S. agents the right to build the airstrip, to use for whatever cause they saw fit.

As Umaña’s book succinctly states: “On that day the bargain was sealed; Piza got his photograph and North got his airstrip.”

In a telephone interview with the Howler, Umaña said U.S. anti-Sandinista operatives had a Northern Front in Honduras and wanted to open a Southern Front in Costa Rica.

“The planes they had, C-123s, couldn’t make the round trip loaded from Ilopango [air base] in El Salvador, make the drop and then get back,” said Umaña, 66. “So they needed a refueling strip and facility in Guanacaste. They told the government something different, they told the Monge government that this was to be used in case the Sandinistas invaded Costa Rica and took out the Liberia airport. But the intention was always the Southern Front.”

Yet those plans were in for a major challenge, with Oscar Arias set to take office May 8, 1986. According to Umaña’s book, Monge and Arias held a meeting previous to the inauguration where Arias was informed of this airstrip plan, in the presence of U.S. Ambassador Lewis Tambs, and Arias said no way.

Arias, who had run on a platform for regional peace, said Costa Rican soil could absolutely not be used as a staging ground for flights to arm rebels in Nicaragua. Tambs promised to abide by Arias’ wishes.

Yet in June 1986, within a month of Arias’ inauguration, the secret airstrip went into operation anyway.

Inside intelligence

Shortly after taking office, Arias and Umaña knew they had a problem on their hands in Potrero Grande. There were already rumors of large planes flying over the area.

Umaña got involved because he was the minister in charge of national parks, and Santa Rosa had long been designated as a key target in his portfolio. Accordingly, on July 4, 1986, he boarded a plane, flew over the site and spotted the large airstrip — over 1,800 meters long, which caused the pilot to exclaim, “This is long as the strip at Pavas!”

Not long afterward, the Tico Times got wind of the story, thanks to local sources calling up to say large planes were flying overhead in places where they didn’t belong.

As a result, Umaña writes, the Arias administration’s Security Council discussed the situation several times, and Public Security Minister Hernán Garrón “felt that he had to take control of the situation.”

So at the break of dawn on Sept. 4, 1986, Garrón personally led a raid of 60 members of the Civil Guard, by land and sea, to see what was going on at this secret airstrip.

“They found a set of well-hidden empty barracks and a couple of dozen 55-gallon drums filled with aviation-grade gasoline,” Umaña writes.

What they didn’t find were any people.

Cat out of the bag

Soon the reporters from the Tico Times and NBC overflew the area and discovered the same airstrip. They contacted Tico Times editor Dery Dyer, who alerted colleagues at Newsweek and the Miami Herald. Word started to spread among the international press, and Dyer started getting calls from the New York Times and other media.

The journalists hired the same pilot the next day to fly them back to the airstrip to get better photos. And they contacted the government for comment. McPhaul took the photos to the presidential offices in San José and showed them to Garrón, who said it was a small airstrip for small planes that the Civil Guard had seized a month earlier.

McPhaul pointed to the large tire marks on the airstrip pictures and said, “Small planes didn’t make those tire marks.”

McPhaul said Garrón angrily responded, “We didn’t know what we were dealing with. We didn’t know if we’d find Contras or armed drug traffickers.”

Though the weekly Tico Times had not yet broken the story in print, the newspaper had let the cat out of the bag by contacting both journalists and government officials. The Arias administration prepared to release a response in a press conference.

Point West reveals that North and his conspirators applied heavy pressure on the Arias administration not to go forward with this press conference, threatening a cutoff of U.S. aid and a cancellation of a meeting between Arias and Reagan.

“The whole Central American press corps descended on Costa Rica,” McPhaul recalled, including reporters from the New York Times, Time and Newsweek. “And they happened to have a press conference for International Press Day, and Garrón had previously been scheduled to be there. It was the best-attended press conference for International Press Day ever.”

When reporters asked Garrón about the secret airstrip, he said the Civil Guard had seized it earlier, but it was part of a “tourism project” run by a Panamanian company called Udall Resources. Udall, it would emerge later, was nothing but a front company for the secret U.S. operation to arm the Contras.

According to Point West, North found out about the press conference and wrote the following memo at 11:23 a.m. the next day. He later tried to permanently erase this memo, but it survived in a backup computer system, leaving his fingerprints all over the scandal:

“Last night, Costa Rican Interior Minister Garrón held a press conference in San Jose and announced that Costa Rican authorities had discovered a secret airstrip that was over a mile long and which was used by a Co. called Udall Services for supporting the Contras. In the press conference the minister named one of Dick’s [Dick Secord’s] agents [real name William C. Haskell, alias Robert Olmsted] as the man who set up the training base for the US….

“Udall Resources Inc. S.A. is a proprietary of Project Democracy. It will cease to exist by noon today. There are no USG [U.S. government] fingerprints on the operation and Olmsted is not the name of the agent — Olmsted does not exist.

“We have moved all Udall Resources ($46K) to another account in Panama where Udall maintained an answering service and cover office.”

The Tico Times published its story two days after the press conference, on Sept. 26, 1986, with Julio Laínez’s photo and an editorial questioning the government’s claims of ignorance about this so-called “tourism project.”

A turn for the worse

These revelations were soon overtaken by a far more serious turn of events. On Oct. 25, 1986, a U.S. Fairchild C-123 cargo plane was shot down over Nicaragua and the lone survivor, ex-Marine Eugene Hasenfus, was captured by Sandinista troops.

Papers found on Hasenfus and in the shot-down plane linked the crew to the head of CIA special operations in San José, Costa Rica, and to safe houses used by crew members in El Salvador. Hasenfus told interrogators, as well as the international press, that he did not work for the CIA but believed he was part of an operation run with the knowledge and consent of the CIA. The U.S. government denied any connection to Hasenfus or the rest of his crew, conveniently claiming that this was a “rogue operation” carried out by private individuals.

“Four days after he had been shot [down],” says Point West, “Hasenfus appeared before the press and declared that he had worked with people he believed to be from the CIA who were operating with the knowledge and blessing of Vice President Bush.”

Hasenfus also said his plane had previously used a clandestine airstrip in Costa Rica as part of its efforts to supply the Contras with arms. In fact, log books showed that Hasenfus had been on a plane that got stuck in the mud at Potrero Grande in early June 1986, though the plane that was shot down over Nicaragua originated from the Ilopango air base in El Salvador.

These revelations rocked the Reagan administration to its core and led to a series of investigations, congressional hearings and criminal hearings. And they sounded the death knell of the clandestine U.S. support for the Contras — which in turn made a comprehensive peace in the region possible.

The peace talks among five presidents were negotiated by none other than Oscar Arias, who steadfastly opposed any use of Costa Rica soil to intervene in the Nicaraguan war — and who for his efforts won the 1987 Nobel Peace Prize 31 years ago.

“By announcing the existence of the airstrip,” Point West says, “Arias had derailed the entire operation and suddenly the assets that North had valued at $4.5 million had become worthless….

“The scandal that had broken out in Washington had weakened Reagan considerably and as Robert Kagan reported, it ‘opened a wide path for Arias to pursue his ambition as a peacemaker that otherwise would have been impossibly narrow.’ ”

The fallout

The most bizarre disclosure to emerge was that U.S. agents sold missiles from Israel to their mutual archenemy Iran to secure the release of hostages in Lebanon and use the profits to arm rebels in Nicaragua. Say … what?

All of this was done to circumvent a congressional ban on U.S. support for any military group in Nicaragua, the so-called “Boland II Amendment” that was in effect from October 1984 to October 1986. In other words, these efforts were completely illegal under U.S. law.

The fallout was humiliating for the Reagan administration, and 14 administration officials were ultimately indicted on various charges, including Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

North was convicted of accepting an illegal gratuity, obstructing a congressional investigation and destroying documents, but his conviction was overturned on appeal because he had been granted immunity to testify before Congress. Ten other officials were convicted on various charges, but in all cases the convictions were overturned, or the officials were pardoned by President George H.W. Bush.

North, who is widely seen as a fall guy for higher-ups, actually said that he believed the arms diversion for the Contras were approved by President Reagan, and that he believed the president’s men were using him as a scapegoat to protect Reagan.

Epilogue

The shoot-down of Hasenfus’ plane marked the end of the covert flights to arm the Contras. A plane identical to the Fairchild C-123 shot down in Nicaragua, intended for the same operation, remained in a hangar at the San José airport, never to fly again.

In an odd postscript to this bizarre story, the owner of the Costa Verde Hotel in Manuel Antonio decided to buy the old Fairchild C-123 at the San José airport and turn it into a bar. In August 2000, Allan Templeton bought the old hulk and shipped it in pieces to a hillside in Manuel Antonio, where it was reassembled and dubbed “the Contra Bar” —the centerpiece of El Avión Restaurant, a major landmark today.

So this plane went from running guns for rebels to serving shots to tourists.

Only in Costa Rica.