Costa Rica’s Viticulture Success Story

Where there’s a will to grow wine, there must be a way — even in Costa Rica. Thus begins the remarkable success story of Virgilio Vidor Viticultura Tropical, a testament to where inspired scientific adventure can lead.

In response to my interview questions about his life’s work, steeped in family tradition, here is what Virgilio Vidor, the vineyard’s scientific investigator and director/proprietor, shared with Howler readers.

Tell us what you are doing now with your grape research work.

For 50 years — initially in Playa Panama, Guanacaste, but much more since 1992 — I have dedicated myself to the genetic creation of autochthonous varieties of “genetically tropical grapes.” This has been achieved by crossing the wild tropical species Vitis Tiliifolia from Central America (and also other tropical and subtropical American and Asian grapes), with the European grape Vitis Vinifera, as well as with other Vitis Vinifera hybrids.

To date, after making between 5,000 and 6,000 hybrids (about four or five million between seeds and new seedlings), I have achieved between 20 and 30 genetically tropical crosses, highly adapted and of good quality. I have been continuously eliminating unsuitable and male plants, especially in my current garden/laboratory in Curridabat, due to not having enough space.

Tell us about your parents’ struggles and the beginnings of the vineyard.

My family ancestors in Italy have always grown grapes and made wines. From cousins and uncles to grandparents, generations of extended family members are part of the legacy and traditions that have been inherited and reproduced.

The culture of grapes and wine was what inspired me and my brother Giuseppe to experiment in Costa Rica. The first thing we did in 1972 was plant 10 types of grapes that we had brought from Italy. That’s how it all started.

Seeing our success, the then-President of the Republic, Daniel Oduber, and the Minister of Agriculture, Hernán Garrón, became interested.

My parents were essential for everything to happen, following us and allowing us to start this adventure together as a family. This gave us strength, love and courage in this scientific adventure. They were very hard times, without rest and with few resources.

Why is your region good for growing grapes?

With support from USAID in the United States and several government institutions in Costa Rica, we started an experimental grape project in Playa Panama. Some varieties at the beginning were successful. Unfortunately, we discovered the existence of an incurable endemic disease, Pierce Disease, which prevented the grape’s successful natural development in our growing location, and in general, throughout the country.

At that time, I realized that the true, and only, way to produce authentically tropical grapes and wine was almost impossible. That is, to create — through crossbreeding — totally new, quality, disease-resistant tropical grapes.

I did this for five decades, including many years working as head of long-term technical assistance missions with the European Union (EuropeAid), and finally with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), supporting integral and sustainable rural development for poor farmers. I also dedicated myself in my free time to grape research.

Ultimately, in these tropical regions, by creating our own grapes genetically adapted to the climate and the territory, a new viticulture was finally attained, with its own concept of natural, cultural and climatic “terroir,” which varies according to the zones. The grape and the wine, likewise have their own typicity and characteristics. I was able to achieve what no one could do in more than 500 years of history.

How do you make your wine? Is it available for purchase?

The tropical wine that I make experimentally in micro-vinifications — it is also a “signature” wine — is a totally new product that does not exist anywhere in the world. It has fantastic colors: pink, white, gold, cherry, ruby, red, amber, salmon, orange, etc. The flavors range from dry to sweet, with some of them having bubbles. They are taken cold and represent the colors, the perfumes, the joy and the tropical essence.

I only dedicate myself to scientific research, but if someone wants to invest and produce grapes and wines, I can gladly advise them. The artisanal wine that I produce is an experimental wine and very small amounts, so it is not for sale to the general public. But sometimes I sell a little to the real amateurs and followers of my work who visit me.

Do you do tours of your plantation?

We offer various types of tours, both touristic and technical-scientific. In addition, training, talks, workshops and technical assistance are given to companies and producers. In addition to some signature wines, grape plants are also available, as well as other special fruit trees. There are also sauces and wines made according to recipes from the time of ancient Rome. And you can find various other products and services of great interest too. Tourists even come from Europe to visit my garden/laboratory, located in Lomas de Ayarco, a residential urban area of Curridabat.

When did you know that you wanted to be a scientist in this field?

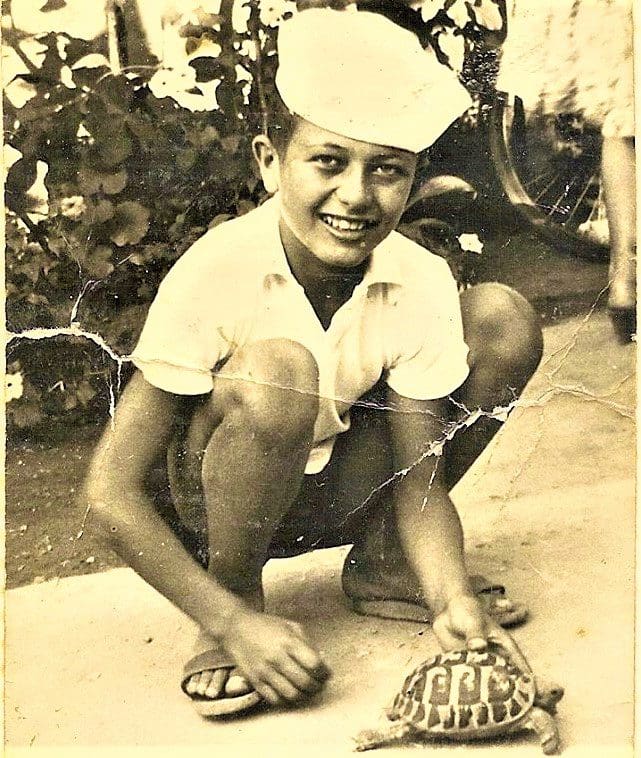

I knew it as a child, in Italy, before leaving for Costa Rica. I dreamed of being a scientist, and my passion was to continuously experiment and investigate, especially with plants. I loved nature.

Virgilio Vidor in 1960, in his home town of Fregene (Rome) in Italy, with one of his pets, a cute Mediterranean land tortoise.

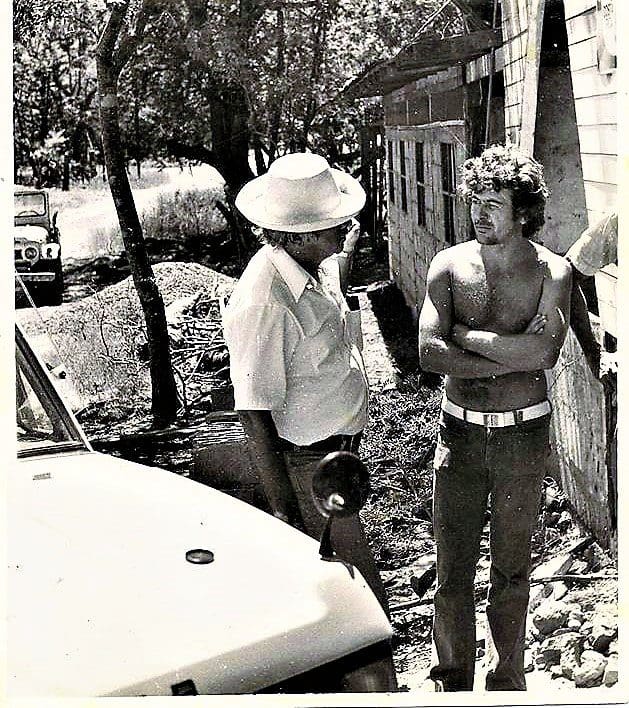

Then-Costa Rica President Daniel Oduber Quirós, a frequent visitor to the Vidor family farm, speaking with Virgilio in Panama Beach.

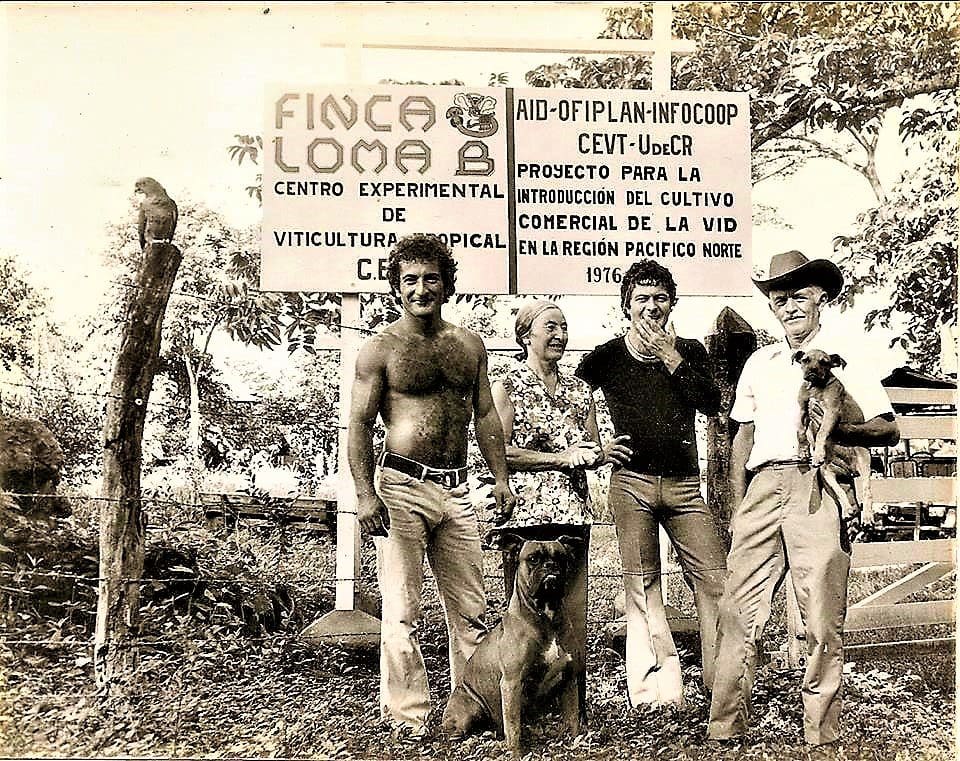

The Vidor family in the 1970s on their farm in Playa Panama, Guanacaste (from left): brother Giuseppe Vidor; mother, Rina Enzo-Vidor; Virgilio Vidor; and father, Fiorenzo Vidor. Their pets, dogs Orso and Milpa, and a Colombino parrot, also appear. The sign above represents the Tropical Viticulture project financed by USAID and the Costa Rica government, of which Virgilio was director.