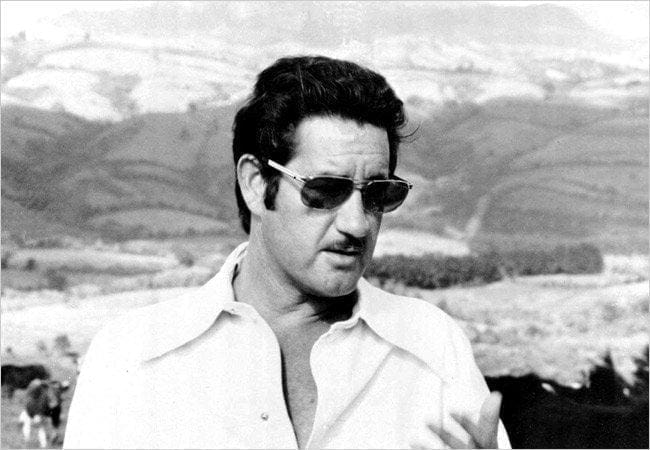

Robert Vesco

If Costa Rica had a Hall of Fame of Foreign Rogues, there would be a statue of Robert Vesco at the entrance.

Audacious, mendacious and thievish to the core, Vesco was the king of fugitive financiers, a master of the game of “Catch Me If You Can.” He was one of the most controversial figures in Costa Rican history, and his friendship with José “Pepe” Figueres became a shameful stain on the legacy of the country’s greatest president.

Fleeing U.S. prosecution after looting a Swiss investment firm of more than $200 million, in 1972 Vesco absconded to Costa Rica, where he bought the 1,000-acre Cabo Velas ranch at the northern end of Tamarindo Bay and Playa Grande.

He built a six-bedroom house with two swimming pools and a bowling alley, paved a dirt runway for his fleet of private planes, and became a hero to the local community by his donations to schools and his generosity to the town of Matapalo.

Figueres, the three-term president who came to power in the 1948 civil war, welcomed Vesco and his millions of stolen dollars. But a change of administration a few years later pulled the rug out from under the charming charlatan. In 1978 Vesco was forced to flee from Costa Rica, and he ended up in Castro’s Cuba.

But he still managed to be condemned to prison in Cuba, where he was trying to hawk a cure for cancer. Perhaps it was fitting that cancer was what finally killed him.

Young scoundrel

Born in Detroit in 1935, Vesco dropped out of high school and moved to New Jersey at 21 to work for a maker of machine tools. He took over the company when it went bankrupt, renamed it International Controls Corp., and became a millionaire by the age of 30.

In 1970 he took over Investment Overseas Services, a troubled Swiss mutual fund firm, for less than $5 million, gaining control of an estimated $400 million in funds.

Under investigation for fraud, he fled the U.S. in 1971, went to the Bahamas, and then came to Costa Rica in 1972 at the invitation of Figueres. In 1972, the Securities and Exchange Commission accused him and his associates of looting the Swiss firm of more than $224 million. He was also accused in 1972 of making an illegal donation of $200,000 to President Richard Nixon’s campaign in hopes of getting charges against him dropped.

In Costa Rica, he hoped to set up a “financial district” where international funds of uncertain origin would be free of scrutiny, according to a 2006 story in the Tico Times. He arrived with a yacht and a private Boeing 707, bought a lavish compound in Curridabat and invested in several Figueres family businesses, acquiring restaurants, bars and casinos.

In Cabo Velas, he purchased the ranch with the airstrip, and he bought Country Day School to create a center for children with learning disabilities so that one of his children could receive education for special kids.

Scandal followed Vesco throughout his stay in Costa Rica, and Figueres was widely criticized for harboring a criminal. Figueres made no apologies, saying in a TV interview, “I wish more Vescos would come to Costa Rica — we need them.”

Just before Figueres’ third term ended in 1974, he pushed through a piece of legislation dubbed “the Vesco law” that gave the president final say on extradition issues. Figueres’ successor and protege, Daniel Oduber, pledged to leave Vesco alone if he obeyed Costa Rican law.

Let’s make machine guns

For Vesco’s next act, he got it in his head to work with Figueres’ son, José Martí Figueres, to finance a factory to make automatic weapons (this in a country with no army). The predictable uproar that followed appears to have been Vesco’s undoing.

The next president elected, Rodrigo Carazo Odio, pledged to expel Vesco from the country, and Vesco fled just 10 days before Carazo took office on May 8, 1978.

Vesco spent the next few years jetting between the Bahamas, Antigua and Nicaragua. In 1982, he very briefly returned to Costa Rica hoping for amnesty from the new president, Luis Alberto Monge, who instead vowed to turn him over to U.S. authorities.

Vesco was detained for just an hour or so at the Liberia airport after a chartered flight from Managua, and the U.S. Embassy was reportedly told to “go and get him if you want him.” But he eluded capture once again, flying out for parts unknown.

Vesco ended up in Cuba, where the Castro government took him in on “humanitarian grounds.” So there he lived out his life in quiet exile without getting into trouble again? Of course not!

What did him in was double-crossing Fidel Castro in a scheme to produce a wonder drug that would cure cancer, AIDS, arthritis and the common cold. In 1996 he was convicted of defrauding a biotech lab run by Castro’s nephew and was sentenced to 13 years, of which he served nine.

Released in 2005, the chain-smoking con artist died of lung cancer in Cuba in 2008 at the age of 71. Or some say he didn’t really die — he actually faked his death and fled to Sierra Leone.

But if so, surely he would have gotten into trouble there too, and we would have all heard about it.