Rohrmoser: from coffee rows to city streets, and the family name that never left

Rohrmoser feels like a neighbourhood that decided—quietly, stubbornly—to keep its cool while the rest of San José got louder. You notice it in the shade first. Mature trees make their own roof over the sidewalks, the air feels a touch softer, and mornings have that calm, purposeful rhythm of joggers, dog walkers, and café staff setting out chairs like it’s a small ritual. But Rohrmoser wasn’t born in a “nice part of town.” It grew out of a very Costa Rican story: coffee land turning into city blocks, and a family name becoming a place name so completely that people forget it was ever a surname at all.

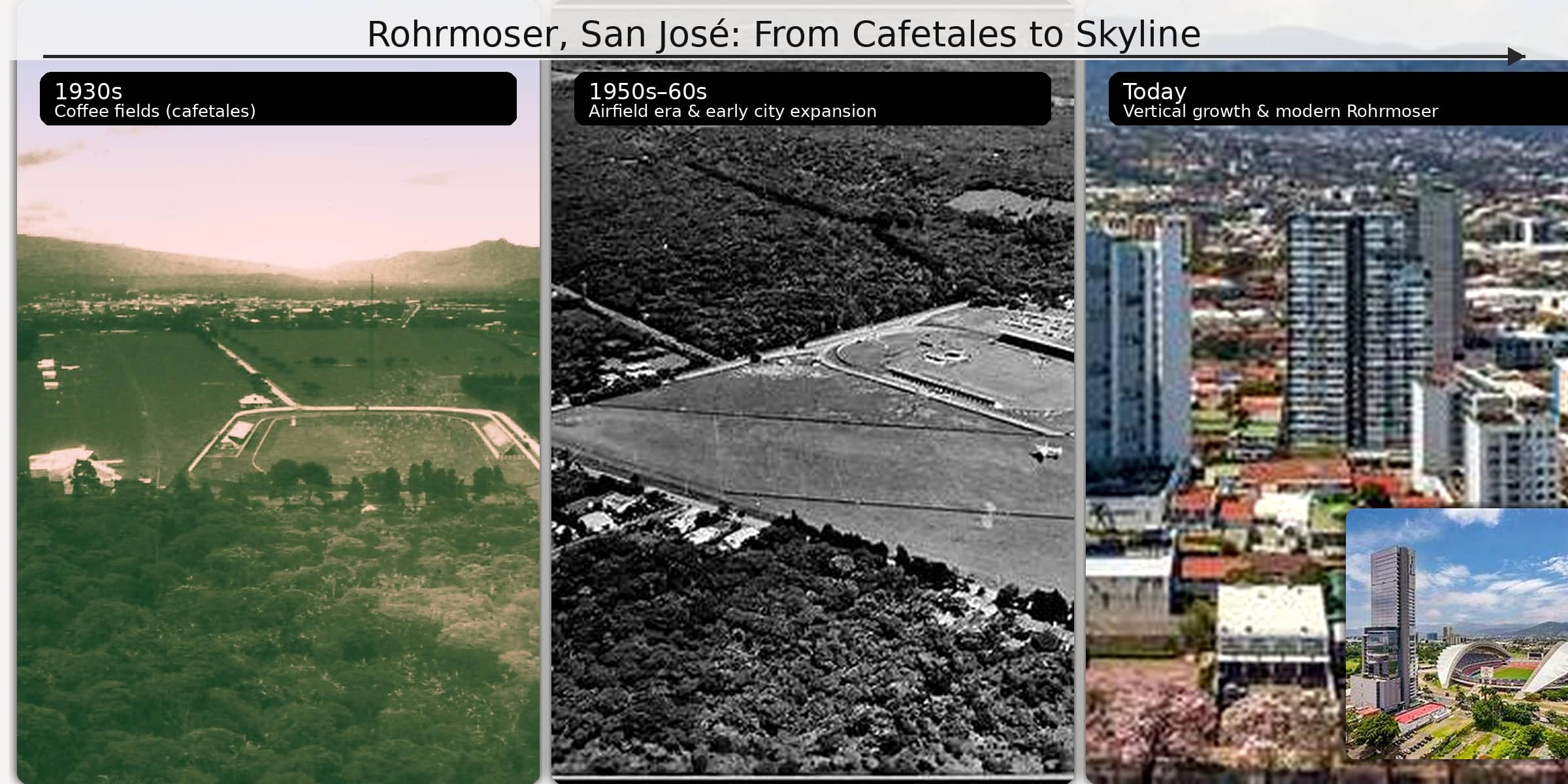

Long before towers and traffic circles, this western edge of San José was coffee country. If you’ve seen the old aerial photos of La Sabana and the surrounding area, the point lands instantly: broad green patches of cafetales rolling out where roads and neighbourhoods would later appear. One heritage publication even captions a 1930s photo as “Rohrmoser covered with coffee plantations,” crediting the image to Román Macaya. (Portal Patrimonio) That single caption is like a time machine—because today, you can stand in Rohrmoser and feel “city” in every direction, yet the land under your feet once produced the crop that built San José’s wealth, influence, and pace.

Aerial view across Rohrmoser when the area was still largely coffee plantations (1930s; photo credited to Román Macaya).

La Sabana airfield in an earlier era, showing the open land that once framed this side of San José.

Historic view of the old La Sabana airport complex (mid-20th century), a reminder of how quickly this zone modernised.

So where does the name come from? The story that matters here isn’t a vague “European family arrived” sketch. The Rohrmoser name is tied to a real line of people who became woven into San José life early enough that one of them left behind a rare, detailed portrait of the capital when it was still young. Francisco “Chico” Rohrmoser von Chamier wrote recollections of his years in San José from 1854 to 1857—written later at the request of historian Cleto González Víquez—and the work is treated as historically valuable because it captures the human and geographic reality of the city during the same period Costa Rica fought the filibusters under William Walker. (kerwa.ucr.ac.cr) It’s hard to overstate how unusual that is: not a grand political narrative, but a lived-in view of streets, society, and everyday life from someone who saw the capital up close while the country’s identity was being tested.

That memoir matters to Rohrmoser’s story because it anchors the family in the city’s memory, not just its property records. When a family name becomes a neighbourhood name, people assume the connection is purely real estate—land owned, land divided, streets laid out. And yes, Rohrmoser absolutely becomes a modern neighbourhood through development. Still, it also carries an older cultural footprint: a family presence in the capital that was substantial enough to be asked, decades later, to write “what it was like” when San José was still forming itself. (kerwa.ucr.ac.cr)

Fast forward a few generations, and you can see the hinge moment when the coffee frontier starts to become something else. The Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica has an authority record for Urbanizadora Rohrmoser S.A., noting that the company was created in 1960 under the name Rohrmoser Hermanos Limitada to develop an urban project in Pavas for middle-class families, and that in 1965 it changed its name to Urbanizadora Rohrmoser S.A. (archivodigital.go.cr). This is the part of the story that turns sentiment into street grids. It’s one thing to say, “This used to be coffee.” It’s another to see the institutional footprint of a planned shift—coffee land gradually giving way to parcels, housing, services, and the kind of neighbourhood structure that makes a place feel coherent decades later.

Old meets new: San José architecture shifting from low historic façades to bold modern lines—exactly the contrast Rohrmoser lives with today.

That 1960s moment also explains why Rohrmoser still feels different from other parts of the city. Planned urbanisation tends to leave behind certain gifts: sidewalks that make sense, blocks that feel walkable, a residential cadence that doesn’t collapse into pure commercial sprawl. Rohrmoser’s “liveability” isn’t accidental—it’s the long echo of a neighbourhood being shaped deliberately, on land that already had value because coffee had proven it valuable first.

Green pockets and big trees are part of Rohrmoser’s day-to-day appeal—cool shade, open space, and a slower city rhythm.

Then comes the next transformation: the modern vertical era. If you’ve driven through Rohrmoser recently, you’ve seen how the skyline is changing—apartment towers rising in a place that used to read mostly as houses and low buildings. A 2025 report in El Financiero describes Rohrmoser’s urban development intensifying with the proliferation of apartment towers, highlighting how the neighbourhood keeps growing upward and how the contrasts within Pavas sharpen around that growth. (El Financiero) That’s Rohrmoser today in one image: old shade trees and new glass, parks and density, a place trying to stay calm while becoming more vertical.

Rohrmoser’s changing skyline: taller residential towers reshaping the horizon.

Vertical growth near Rohrmoser and La Sabana—modern living rising where open land once dominated.

The La Sabana corridor today: the National Stadium and nearby high-rises show how this side of San José keeps evolving.

And yet, the coffee origin still shows up if you know how to look for it. It’s in the way Rohrmoser sits beside La Sabana’s long historic corridor, the way the west of San José used to be “productive green” before it was “urban green,” and the way a family name stayed attached through the shift from agriculture to modern living. The coffee farms didn’t just disappear; they were converted—economically, physically, socially—into the kind of land that could hold a neighbourhood people now choose as a base for work trips, long stays, and day-to-day city life.

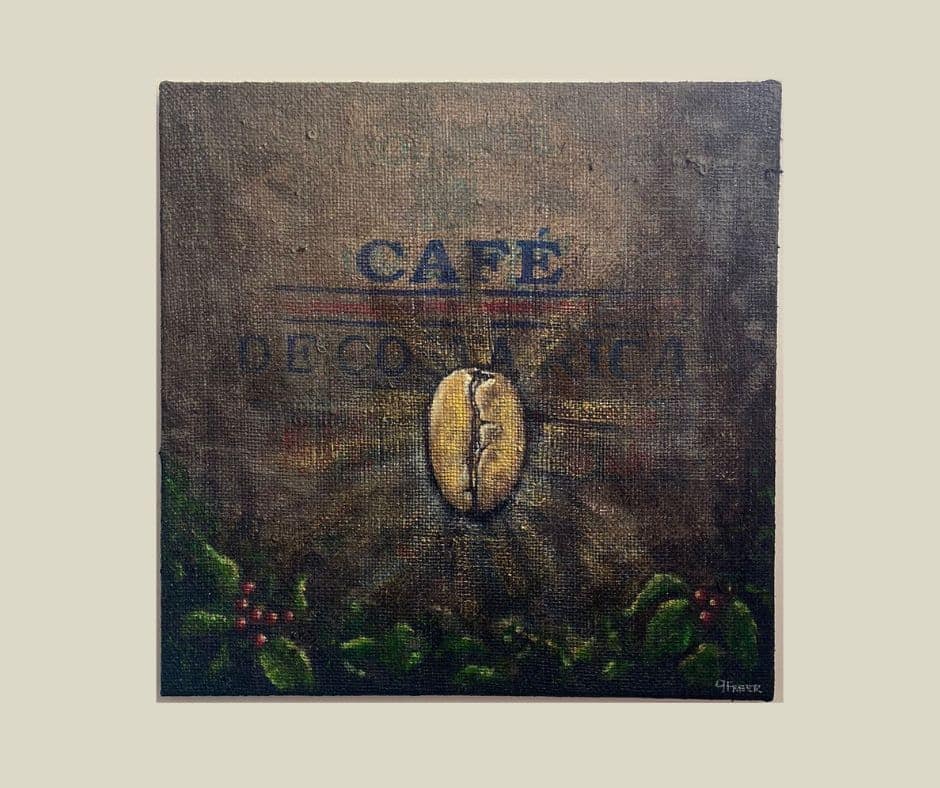

A public coffee monument—proof that coffee still lives in the city’s memory, even where the fields are long gone.

Spend a morning in Rohrmoser and you can feel that layered history without reading a single archive. You’ll pass a café that looks like it’s been part of the street forever, then glance up at a tower that clearly hasn’t. You’ll see an older home with a garden that suggests a different era of space, then an apartment entrance with security and sleek lines that suggest the future arriving fast. The charm is that Rohrmoser doesn’t feel like it’s pretending to be historic. It feels like it’s simply been through phases—coffee, development, densification—and kept enough softness in the landscape to remain recognisable as itself.

If you’re telling the story of Rohrmoser, that’s the hook worth leaning on: a neighbourhood that began as cafetales, was shaped into a middle-class urban project in the 1960s, and is now climbing upward—while still carrying a family name linked to one of the most textured personal accounts of San José’s mid-19th-century life. (Portal Patrimonio) Rohrmoser isn’t just a place to live. It’s a living example of how Costa Rica’s capital became what it is—one converted coffee field at a time.

A single image that carries a whole country’s coffee story: “The Sacred Bean” by Costa Rican artist and designer Gloriana Freer Rohrmoser. Painted in acrylic on an authentic Costa Rican coffee burlap sack (60 x 60 cm), it lets the rough weave, worn fibres, and stamped lettering become part of the artwork—like a quiet nod to every bean that ever travelled out of these hills.

This artwork is available.

To enquire or purchase, contact Gloriana Freer Rohrmoser: glorianafreer@gmail.com

More details here: https://howlermag.com/the-sacred-bean/