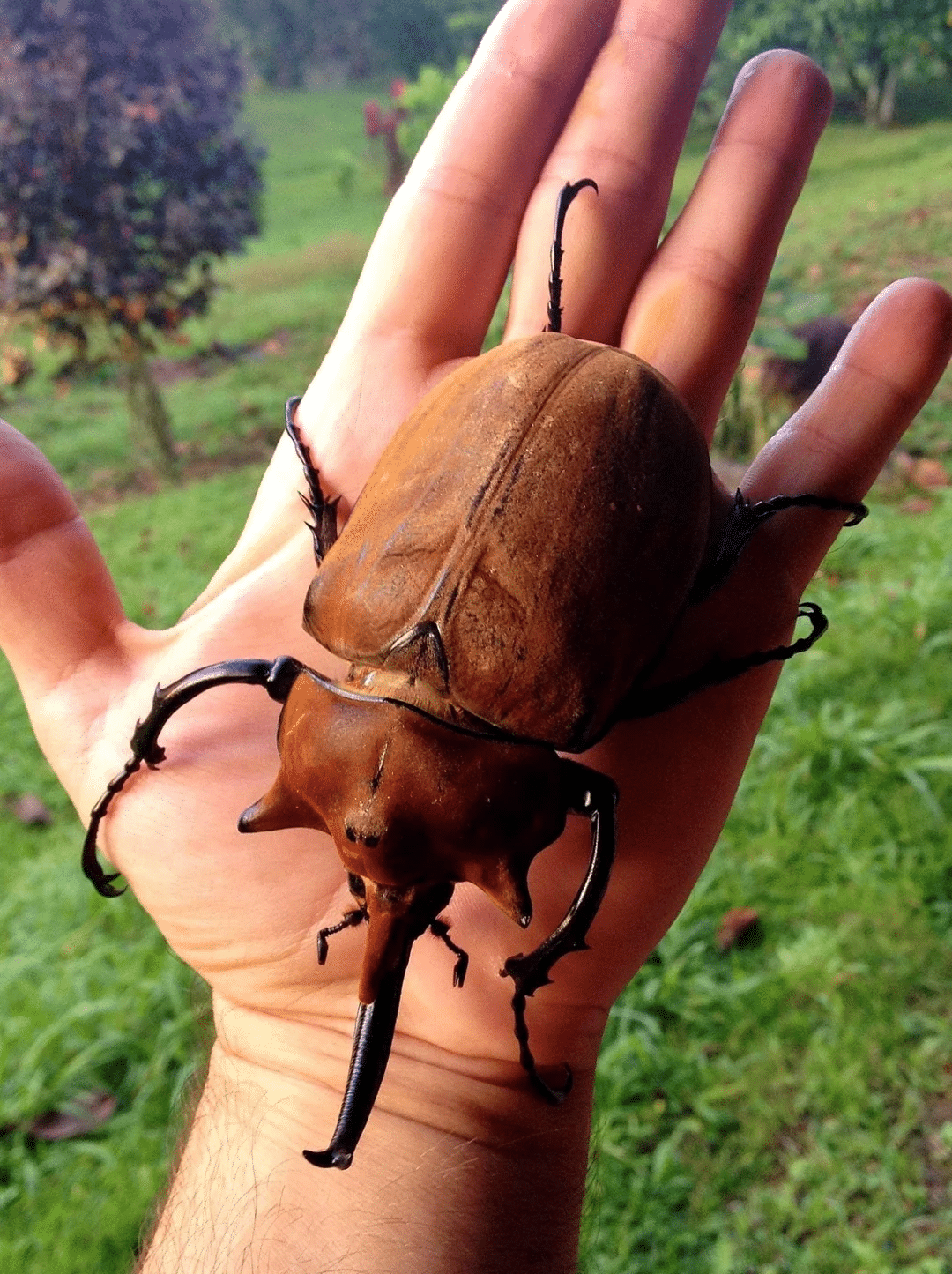

Costa Rica is full of big characters—scarlet macaws that sound like rock bands, surfers who swear the next set is “the one”, chefs plating mango with chilli like it’s confetti, and beetles the size of a child’s fist patrolling the rainforest after dark. The elephant beetle is one of those show-stoppers. Spot one on a night walk and you’re suddenly in the middle of a proper Costa Rican mash-up: Adventures under dripping leaves, culture and folklore in the guide’s whispered stories, entertainment in the sheer spectacle, wildlife at its most outrageous, and even threads to real estate, business, and food—because healthy forests underpin property values, tourism jobs, and the fruit trees we love to eat under. This is a creature that proves nature isn’t a sideshow; it’s the main event.

What exactly is an elephant beetle?

An elephant beetle is a giant tropical scarab (Megasoma elephas) found in Central American rainforests, including Costa Rica’s lowlands.

These beetles typically reach 6–8 cm (2.5–3+ inches) and males can be hefty; their glossy, often dust-coated bodies and the males’ dramatic forehead and thoracic horns give them their “elephant” reputation. Mostly nocturnal, they haunt tree trunks, sap flows and fallen fruit from the Osa Peninsula to the Caribbean slope.

Why are male elephant beetles horned?

Only males grow horns, and they use them as levers to wrestle rivals for access to females.

These slow-motion sumo bouts look theatrical but are finely tuned: the horns help flip or push a competitor from a trunk. Females, by contrast, carry only small bumps—weight saved for egg-making rather than jousting.

What do elephant beetles eat?

They feed mainly on tree sap, fallen fruit, and decaying wood.

That menu makes them superb recyclers of rainforest nutrients. Adults sip sap and fruit juices; larvae—white, C-shaped grubs—spend years chewing through rotting timber and leaf litter hidden inside tree hollows or arboreal compost.

How do they help Costa Rica’s environment?

Elephant beetles accelerate decomposition, build soil health, and spread forest microbes.

-

Nutrient cycling: Larvae pulverise dead wood into fine, microbe-rich frass that plants can reuse.

-

Soil aeration: Tunnelling opens tiny passageways for water and roots.

-

Microbe & fungus dispersal: Moving between logs and sap sites helps carry beneficial fungi and bacteria across the forest.

-

Food-web support: Adults and larvae feed predators—from kinkajous to owls—keeping rainforest dinner services running on time.

For Costa Rica, that behind-the-scenes labour supports healthier watersheds, more resilient fruit trees, better wildlife viewing for tourism, and long-term forest value that underpins eco-lodges, farms, and communities.

Where and when can you see them in Costa Rica?

Night walks in mature, humid forest—especially after rain—offer your best chance.

Look for them:

-

On tree trunks and lianas: Follow the glint of sap and “sniff” of fermenting fruit.

-

Near fallen mango, guava or wild figs: Sticky buffets attract adults.

-

During wet season nights: Activity spikes with humidity and food abundance.

Tip: Use a red-filtered torch and keep a respectful distance; they’re powerful, and handling is stressful for the beetle.

How do they grow from egg to armour-plated adult?

They spend most of their lives as larvae hidden in arboreal compost or decaying wood.

-

Eggs: Laid in rotting plant matter or disused nests tucked in tree cavities.

-

Larvae (2–3 years): Each can consume several pounds of decomposing wood and leaf litter, doing the forest’s heavy lifting.

-

Pupa (6–12 weeks, sometimes longer): Inside a chamber, the grub restructures into a beetle.

-

Adult (1–3 months): A short finale focused on feeding, flying, and mating.

Are they dangerous?

They’re not venomous and prefer to be left alone, but they can deliver a painful pinch if mishandled.

Treat them as you would any wild animal: admire, photograph, and avoid contact. If you brush one on a trunk, give it space—those legs grip like crampons.

What threatens elephant beetles?

Habitat loss, collection for the pet and curio trades, and local harvesting pressures all take a toll.

-

Deforestation & fragmentation: Fewer mature trees mean fewer sap flows, hollows, and rotting logs—critical nursery sites.

-

Illegal collection: Demand for “giant beetles” as pets or ornaments harms populations.

-

Over-tidy landscapes: Removing dead wood in parks or private lands erases larval habitat.

Costa Rica’s protected areas help, but private landowners and lodges can make a huge difference by leaving some dead wood, planting native fruiting trees, and teaching guests responsible viewing.

Did scientists really make “cyborg” beetles?

Yes—research groups have experimented with implanting micro-electronics in large scarab beetles to study flight control.

In proof-of-concept work, electrodes placed during the pupal stage allowed limited influence over wing muscles after emergence. It’s a glimpse into bio-robotics, though not something seen outside laboratories, and it raises important ethical conversations about how we learn from wildlife.

How do elephant beetles connect to business, real estate and food in Costa Rica?

Healthy beetle populations signal thriving forests, which sustain tourism brands, raise the value of nature-adjacent properties, and support fruit productivity.

-

Tourism & adventure: Night walks with charismatic giants make unforgettable guest experiences.

-

Real estate: Properties bordering intact forest enjoy cooler microclimates, birdsong, and biodiversity kerb appeal.

-

Food & farming: Beetles’ soil-building work benefits cacao, coffee, and fruit trees central to Costa Rican cuisine and exports.

Protecting beetles isn’t niche—it’s smart national economics.

How to see them responsibly (quick guide)

-

Go with certified naturalist guides on established trails.

-

Use low-intensity, red-filtered lights to reduce stress.

-

Never collect or handle adults or larvae.

-

Leave fallen wood and leaf litter when managing private land.

-

Support lodges and operators that invest in habitat restoration.

FAQ

Are elephant beetles endemic to Costa Rica?

No. They range across parts of Central and South America, but Costa Rica offers excellent viewing thanks to accessible, protected forests.

Do they bite or sting?

They don’t sting or carry venom. A defensive pinch or scrape can hurt, so admire without touching.

Can they fly?

Yes. Despite their size, adults open their wing covers and buzz between trees on warm, humid nights.

What’s the best month to look?

During the rainy season and early green season, when sap flows and fruit availability peak—though local conditions vary by region.

How can I help?

Choose eco-certified tours, avoid buying insect curios, plant native fruiting trees, and let some dead wood remain on your property.

A last word from the forest

If you ever needed proof that the rainforest runs on quiet workers, the elephant beetle is it: an armoured composter turning fallen giants into new life, one mouthful at a time. Protecting them keeps Costa Rica’s great wheel turning—adventures richer, wildlife wilder, plates tastier, businesses sturdier, and homes closer to living green.

HOWLER Monkey

Bullet Ants, Pain You Don’t Want to Feel

Tree Boas

Toucan Species

Jaguars: Cool Cat has crucial Place in Ecosystem

Coati

Leatherbacks: a close-to-home concern

A Unique Mix of Animals in Costa Rica

The Costa Rican Coral Snake