The Making of Lake Arenal

- DEC 31, 2019Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/howlermag/public_html/old/wp-content/themes/new-paper/includes/general.php on line 193

Your Lead Paragrpah goes here

The Making of Lake Arenal: Life-Changing Upheaval for Two Small Communities. Forty years ago, Costa Rica inaugurated the largest public works project in its history — damming a river and flooding a valley to create the second-largest lake in Central America and increase the country’s hydroelectric potential by 50%.

But for 2,500 people in two communities at the bottom of that valley, Arenal and Tronadora, it meant leaving behind their homes, schools, churches and even their dead before the floodwaters destroyed everything in 1979.

Two brand-new communities arose on higher ground to replace these towns, one called Nuevo Arenal and one still called Tronadora. There were some advantages for the relocated residents — new homes, churches, schools and community centers, streets with sidewalks and gutters, improved sewage disposal, and for the first time, grid electricity and telephone service.

Yet for many families, it was a heart-wrenching upheaval and the end of a simple way of life they had enjoyed for decades.

“Arenal had an important community as far as cattle, dairy, lumber,” said Janeth Gutiérrez Briceño, 65, who moved to Arenal in 1977, just as the relocation was under way. “There was a very nice wooden school, an education and nutrition center, a church, a Banco Nacional, a dance hall.”

Every human being living in that basin

would have to be moved elsewhere.

In the mid-1970s, the Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad (ICE), the national electricity company, came to town and broke the news that all of this was going to be flooded and that everyone would have to move. Residents were given the option of trading their old homes for new homes in the relocated towns, or they could accept the assessed value of their homes and move away from the region. The only option they weren’t given was to stay here.

“Some opted to sell and leave town,” said Gutiérrez, a retired preschool teacher who now owns a bakery and mini super in Tronadora. “There were a lot of people who didn’t want to leave, and they had to leave their homes, with their chickens, pigs and everything.”

As the relocation wrapped up, the towns held a bittersweet goodbye party, or perhaps more of a wake.

“And I remember they did a goodbye dance, and some were drinking, some were crying, some were singing, some were shouting,” she said. “It was a big get-together to say goodbye to the old town. … And there was a cemetery there, too, that was flooded.”

Nobody had any choice in the matter, least of all the dead.

The project

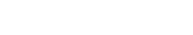

ICE engineers had long noted that this valley to the north of Arenal Volcano would be ideal for building a reservoir because it was a large, flat basin with abundant rainfall. It was also 500 meters higher than the plains of Cañas — a gradient that would allow for hydroelectric production through the force of gravity.

The Arenal River flowed naturally through a gap between two mountains. If that gap were dammed, this huge basin would be flooded, creating a reservoir of 75 square kilometers. It would be the second-largest lake in Central America after the immense Lake Nicaragua.

In terms of total area, it was the equivalent of flooding everything between Heredia and Cartago, including much of the city of San José.

This reservoir would enable Costa Rica to increase its hydroelectric production by 600,000 KW — enough to supply 40% of the entire country’s electrical needs. And when the water’s work was done, it could still be used to irrigate the dry fields at the bottom of the slope.

The first step was to build a 560-meter tunnel to change the course of Arenal River. Once the river was diverted, construction on the dam could begin, with millions of cubic meters of sand, clay and gravel trucked in as fill.

When the dam was complete, the river would be restored to its original course, the flooding of the basin would begin, and giant turbines could start generating massive amounts of electricity.

But first, every human being living in that basin would have to be moved elsewhere.

Where to rebuild?

Residents of the two towns were given a handful of options on where to relocate, and after weeks of discussion a vote was taken. Arenal (which means “sandy place,” referring to the ashy slopes of the volcano) chose a location on the northeastern edge of the basin called Santa María, and here construction of Nuevo Arenal began in 1975.

Tronadora (which means “thunderer,” and could be a reference to either volcanic eruptions or to a loud river nearby) chose a site on the other side of the basin near the current San Luis, and construction also began in 1975.

Leonardo Alvarez Picado, 72, was born in a now-flooded village called Caño Negro in 1947, and he also lived in Pueblo Nuevo (which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption), and in old Arenal and old Tronadora. Today he runs a restaurant on the main street in the new Tronadora, and can sometimes be seen trotting around town on one of his 10 horses.

Leonardo Alvarez Picado, 72, was born in a now-flooded village called Caño Negro in 1947, and he also lived in Pueblo Nuevo (which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption), and in old Arenal and old Tronadora. Today he runs a restaurant on the main street in the new Tronadora, and can sometimes be seen trotting around town on one of his 10 horses.

“Arenal was a big town — it had nice restaurants, dance halls, a church, and was very good for commerce,” he said. “There were cattle and good, fertile soil, the best you can imagine.

“The majority of the people had their own lives, their fincas, their milk cows, pigs. The people lived well. We made cheese and sold it in Arenal every week, and that’s how we made the money for other expenses — food, school and everything.”

Alvarez recalls that few people mounted any resistance to ICE’s plans — “the people were like asleep,” he said.

Looking out on the soccer field across from his bar, he said, “These lands were a lot worse than Arenal, many times over, commercially. This is OK to live in, but to compare this to old Arenal and Tronadora, it’s not even their shadow.”

‘Ruined completely’

He says when ICE came around telling people they would have to leave, some people were nervous, but they raised no real opposition.

“A lot of people thought that selling was a good option,” he said. “But there were old-time farmers who were ruined completely, families that were born there … they were ruined completely because they had never left this place to go try something somewhere else.

“So the money they got, even though they had huge fincas and 200 cows or 50 or 100 — that money, a few years later, was just enough to buy their daily food.”

Gutiérrez, the former preschool teacher, said, “Yes, people were happy with their new houses, because maybe their old ones were ugly. But with a new house and no food and no work, that’s no good, right?”

She said one of the worst outcomes of the relocation was that ICE was not required to pay one cent in taxes to the municipality in nearby Tilarán — erasing big sources of revenue formerly paid by the now-flooded fincas.

“They should have left a minimum percentage of their earnings for the municipality to invest in development projects that could generate employment, so that the young people wouldn’t have to leave,” she said. “A lot of the youth here go to San José to work and they never come back. There’s no work here.”

Gutiérrez feels that the electricity project benefited an entire country but impoverished the rural community that made it possible.

“We were very happy to develop the country, but at the expense of a small town,” she said. “We ruined one person to enrich many.”

Lake Arenal today

Today Lake Arenal is one of the most beautiful areas in Costa Rica, surrounded by verdant tropical forest teeming with abundant wildlife. The lake itself is blue and gorgeous, and you’d never guess it was created by human beings if not for the huge dam on its eastern edge.

Lake-view homes are prized by retirees, families and vacation renters, and Lake Arenal is a major draw for fishing, windsurfing, catamaran cruises and stand-up paddling. It’s surrounded by pea-green hills topped with picturesque white windmills (another major source of electricity generated by the region).

Nuevo Arenal is a smallish but thriving community with hotels, restaurants, stores, banks and a gas station, located along a paved highway between Tilarán and La Fortuna, the tourism capital of the region.

Tronadora is not a big magnet for tourism, nor is the much larger Tilarán, but both are immaculate towns with nicely paved streets and a wide array of services. The locals on the western side of the lake long for the day when a bridge will be built across the Río Caño Negro near El Castillo in the southwest, creating a major shortcut to La Fortuna and the wealth of tourism opportunity it represents. Even better, hopefully someday the road on the western edge of the lake will be paved.

For now, these towns get along the best they can — the older residents perhaps looking back on fonder days, the younger generation trying to make the most of the only towns they’ve ever known.

But when the wind, rain and fog roll in over Lake Arenal, if you use your imagination you can almost see the ghosts of the towns that preceded them hovering in the mist above the waters.

Read more about the Lake Arenal and the towns around it here.