Feature Article: Where have all the Leatherbacks Gone

- MAR 07, 2017Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /home/howlermag/public_html/old/wp-content/themes/new-paper/includes/general.php on line 193

Your Lead Paragrpah goes here

The Science

Not so long ago, the giant, majestic leatherback turtle (Latin: Dermochelys coriacea; Spanish: baula) swam all of the world’s largest oceans and populated their birthplace beaches abundantly. Weighing 600-2000 pounds, measuring 6 feet, and with an expected lifespan of around 100 years, their reptilian ancestors predated the dinosaurs, already roaming the earth more than 100 million years ago.

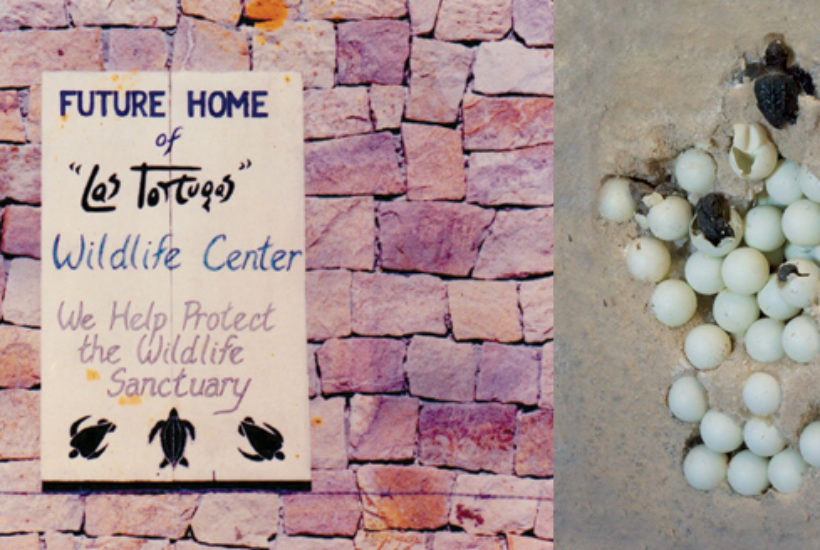

Male turtles spend their entire lives at sea. An adult female will swim 1,000 – 1,500 miles, just to turn around and return to her birthplace to nest. At the right time of year, which around here is late October through late February, she comes in under the cover of darkness, usually using the high tide to help her massive body more easily trudge up the beach to the softer sand. Here she digs a hole, deposits 50 to 90 eggs, and covers them carefully. As a decoy for predators, she also makes a fake nest nearby. She’ll lay 4 to 7 nests per season.

Turtle eggs take 60 days to hatch. One fun fact is that their sex is determined by the egg temperature: Below 85 F results in males, above 85 F you get all females, and at 85 F a mix of males and females exits the nest. The baby turtles need to emerge under the cover of darkness. Lights on the beach can easily disorient them and cause them to travel in the wrong direction, meaning they may not make it to the surf before the sun comes up, and certain death.

Playa Grande’s legendary leatherbacks

Back in the day, these beaches were literally loaded with thousands and thousands of turtle eggs, the result of an estimated 2,000 unique turtles that nested multiple times in Playa Grande every season. The leatherback turtle coexisted peacefully among local residents.

Carmen Jaen Lopez, 55, was born in Playa Grande along with 7 siblings. Coming from a hunter-gatherer-type background, her family would gather turtle eggs to sell for grocery money. They would fill huge sacks, with maybe 250 eggs each, every night, then transport them by horseback. The turtles were so abundant, this was done with the easy consciousness of fishing today. Other reports say people loaded eggs off the beach in ox-carts. Despite new laws preventing their removal, cookie companies even came in with heavy machinery under cover of darkness—until the media reported on them.

The path to their protection

In 1974, Louis Wilson left behind a promising career as a Florida psychologist in favor of the pristine beauty and epic waves here. Wilson and his brother, Randy, were the first gringos living in Tamarindo. Surfers would occasionally stop by, but no one else was around except the locals. “The community was on the edge of starvation,” recalls Wilson, a salty, seasoned expat. “The very next year, Puka shells were discovered here. An hour’s worth of collecting these shells could bring $1,000. So people came from all over for the shells. That put Tamarindo on the map.”

Turtles were abundant. “One time a turtle came into the Lobos bar and made a nest right inside the bar,” recalls Wilson, squeezing a whole lime on his papaya then giving it an even layer of salt. “There were sand dunes, and Tamarindo had no one on the beach. It was a perfect nesting ground. Pristine.” Wilson reports having seen 50-100 turtles nightly between Tamarindo and Grande, of all varieties that nest here, but primarily leatherbacks. Other turtles include Ridleys, Loras, Greens, and Blacks.

In 1978, authorities cleared the sand dunes for road construction. That was the Tamarindo turtle habitat. From then, the turtles came mainly to Playa Grande. But people came to Tamarindo wanting to see the turtles. So Wilson would boat people across the estuary at night. He didn’t know it, but this was the beginning of what today is known as eco-tourism.

In 1978, authorities cleared the sand dunes for road construction. That was the Tamarindo turtle habitat. From then, the turtles came mainly to Playa Grande. But people came to Tamarindo wanting to see the turtles. So Wilson would boat people across the estuary at night. He didn’t know it, but this was the beginning of what today is known as eco-tourism.

Things began shaking up in the 80s and Wilson began his crusade to save the natural habitat of the area. Economic forces, i.e. developers, were pushing for control of the estuary and Playa Grande, and seeing dollar signs, the local community didn’t believe the turtles were worth saving. Impassioned Wilson brought an economic argument, showing how keeping nature intact would both bring tourists and increase surrounding land values, pumping up the economy in two ways.

In the meantime, the people came. In droves. Everyone wanted to see the turtles. Politicking by day, by night Wilson and his partner Marianela Pastor, a Tica who had grown up camping in these parts and compelled to save them, were running turtle tours out of their Hotel Las Tortugas and serving 150 dinners every night. An employee from that time, Matapalo native Yohana Paniagua Obando, recalls “You would be finished working at 9:00, all cleaned up and ready to go home, and here would come another bus of [25-40] people to see the turtles. So you would have to open everything back up again, start chopping again, and go back to work.”

Also in the 1980s, another player entered the turtle conversation. The Leatherback Trust established itself as a research institution, and built a site right next to Hotel Las Tortugas in Playa Grande.

Wilson and Pastor, with the help of Senators Rudolfo Brenes and Gladys Rojas (dec.), worked exhaustively for years to gain protected status for the area. In 1990 the Tamarindo Wildlife Sanctuary was finally passed into law, forever protecting Playa Grande. Wilson wrote that law, and Rojas helped gain senate approval. In 1993, the estuary was recognized by Ramsar, the international body that identifies the world’s most important wetlands, as a critical wetland for the planet’s ecosystem. In 1995 the national park Marino Las Baulas was officially established, and the Ministero de Ambiente y Energía (MINAE) took over care of the park and the welfare of an estimated 2,000 healthy female leatherbacks, according to Wilson and Pastor’s estimation. MINAE biologist Ademar Rosales Ruiz says the park they manage, Marino Las Baulas, measures approximately 26 ha of marine and 900 ha of terrestrial property, and confirms that their primary purpose is the care and welfare of the leatherback, followed closely by the estuary.

Wilson and Pastor kept pushing for increased protection for the area. “But by that time, Tamarindo had become a party town, and ecotourism took a back seat to unbridled development,” laments Wilson.

The legendary leatherback nesting site Playa Grande still attracts a lot of tourists hoping to see the turtles, and Wilson still runs Hotel Las Tortugas, employing all local people. At press time, 12 different turtles have returned to Playa Grande this nesting season.

What happened to the leatherbacks?

It turns out 1995 was about the last time anyone really saw an abundance of leatherbacks pretty much anywhere. Some sources say the species has declined by 98%.

These numbers beg the question of what happened? The answer to that depends entirely on who you ask. Some reasons observed include: unethical Pacific fishing fleets, largely by Asian nations; local fishermen callously slaughtering turtles coming home to nest; death by choking on plastic, mistaking it for food; bright lights on the beach; devastated habitat; egg poachers; MINAE mismanagement; people’s dogs; free-wheeling scientific research programs; authorities not responding to calls of poaching and slaughter in a timely manner if at all; no reporting of slaughter and poaching due to fear of retaliation; ocean current changes; moving eggs and handling hatchlings; raccoons that arrived with the hundred or so Palm Beach residences; and ocean floor changes. Perhaps it was a combination of a lot of these elements, and maybe some not on this list. Humans were probably involved in the equation, at least at some level. The leatherbacks survive just fine for 100 million years, then in the last 20 they nearly disappear? I smell a human hand in there somewhere.

The bottom line, however, is that the leatherbacks are nearly gone from Playa Grande. Rather than point fingers, it’s more productive to focus on what we can do, which is live sustainably in every way and enforce sustainability when we observe its violation. For example, gas-powered boats, leaving behind fossil fuel waste and tearing up the crucial marshy bottom with lethal propellers, have no business in an internationally protected estuary deemed critical to the planet’s ecosystem. This is not the Disneyland Jungle Tour. Take a canoe. Another example is eating snacks fried in palm oil, as most here are, contributing to destroying habitats and many species. The orangutans shouldn’t have to die for your potato chips. Homemade chips are delicious! Maybe we can’t stop this type of destruction, but we can choose to not support it. It’s not easy to live responsibly in an irresponsible world. And for heaven’s sake please do not feed any of the animals. Just leave them alone and stay out of their way. They do not exist for our amusement and deserve our full respect.

It is up to us to be the responsible ones, as consumers. We cannot leave it to industry to do the right thing, ever. We have to think, and to question businesses’ sustainability practices, knowing that businesses will always exploit and destroy in pursuit of profit. Greed knows no conscience. They will exploit whatever we pay them to. We have to support the responsible ones.

If we had had this conversation a thousand leatherbacks ago, this story might have a happier ending. At this point, these numbers are screaming at us to behave responsibly and show some respect for all the plant and animals species with which we coexist. Our own comfort and convenience should never trump the health and well-being of others, human or not.

Please support the Ocean Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund.